Originally published in Overland Journal 2007

See also: VW Taro pickup

SEQ Intro

Part 2

As with most of us, the blanks on the map have a certain attraction; who knows what you’ll find in the places nobody goes. And though I’ve been traveling in the Sahara since the early 1980s, the desert there stills holds plenty of blanks for me. Most Saharan travel occurs in the centre, a spectacular region of plateaux, sand seas and mountain ranges filling most of Libya, Algeria and Niger; the homeland of the Tuareg nomads. To the east was the so-called Libyan Desert covering parts of Libya, Sudan and Egypt. I’d been there too.

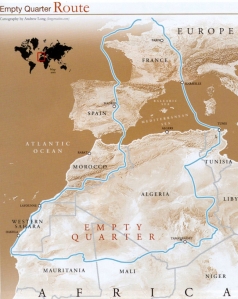

But there was one region where no one went, which no tracks crossed and where even wells could be counted on the fingers of one hand. Among other names it’s known as the Majabat al-Koubra or ‘Empty Quarter’ and it spills over the Mauritanian, Malian and Algerian borders a hyper-arid half -a-million square miles of not much at all.Part of the reason Saharan travellers avoid it these days was the higher-than-average chance of getting robbed. The Malian part of the Empty Quarter had in the last two decades become a runway for smugglers taking drugs, cigarettes, arms and lately kidnapping tourists. A German guy I knew who’d led an expedition across the Quarter had his group cleaned out by bandits in Mauritania, while unrest by the Kel Iforhas Tuareg in the northeast meant travellers were at risk on even the regular route south to the Niger River.

At this time banditry was a relatively new, or revisited phenomenon in the Sahara and I’d heard of or had my share of tense or close encounters since the nomadic rebellions and Islamicist activities disrupted Saharan tourism. But smugglers usually avoid all contact on the move, while bandits tend to prey in areas where they can be sure to make a hit: recognised tracks or events like the Dakar Rally, natural bottlenecks or border areas where they can make a quick getaway. By travelling off-piste in an uncommon orientation we should stay below their radar.

Nevertheless without local knowledge the run would still be too risky as we had to bend a few immigration rules to make it happen. What I needed was a local guy with good but not necessarily legitimate connections; a guide unlike most Saharan guides who was happy to get out of his comfort zone rather than follow the well-worn tourist tramlines.

I had my eye on a guy who ran an agency in Algeria and during a trip with him I put the question: how did he feel about joining me on a 1300-mile traverse across ‘Le Quartier Vide’ from Atar in Mauritania across northern Mali to Bordj Moktar in southern Algeria?

Mohamed sucked in his cheeks, raised his eyebrows and with a nomad’s typical understatement replied “C’est loin…” [it’s a long way]. He maintained good connections out there from his own smuggling days but such a trip wouldn’t be cheap, there were ‘lots of mouths to feed’. How about nice European spec turbo-diesel 80 series Land Cruiser which were then unknown in Algeria, I asked? That would do nicely. We had a deal.Ten months later I blasted across Algeria in a burgundy 80VX, from Algiers 1000 miles south to a semi-abandoned mud-brick trading post in No-Mans-Land along the north Malian frontier called In Khalil. You won’t find it on any map, even Google Earth barely picked it up, but here at a depot nicknamed L’Ambassade (below left) fuel, flour and other ‘soft’ contraband slipped out of much-subsidized Algeria into remote northern Mali.

The introduction was made and with the help of sat phones the guys at the Ambassade would offer a key supporting role if we got in trouble in northern Mali. The 80 got picked up to have it’s identity reprofiled and I flew home to get ready for the main event.

I’d never tried to pull off anything like this before – something I might have once dismissed as a stunt. But part of the appeal of pursuing adventurous goals is to push yourself a little further every time, as your experience and confidence grows.

To help subsidise the cost I invited a couple of others to join me. Roger and Sue’s ageing 80VX nicknamed ‘Eric’ were up for it. They’d joined me on my first tour to Algeria in 2000 following the turbulent 90s. Meanwhile gardener Ron with an old 60 had a bit of desert previous too and was up for it. A few other parties I turned away, some rather too attracted to the clandestine nature of the trip, while another wrote himself out by asking if we could pick up any good ganja along the way!

Both parties understood clearly that their vehicles and, at worst, their liberty were up for grabs, but recognized that actually getting shot was as likely back home in the UK unless we too produced guns – a dumb idea even if we could get them. Instead, Mohamed would be our negotiator, something which on a good day the genial former nomad could manage well.

On my recommendation Mohamed decided not to risk the plush VX I’d paid him with, but planned to use an old, ex-police Land Cruiser which he’d had converted to take the ‘African’ IHZ diesel engine. We planned to meet up in Atar, Mauritania in early November 2006.

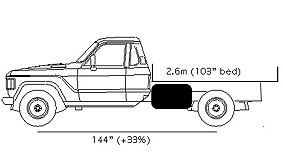

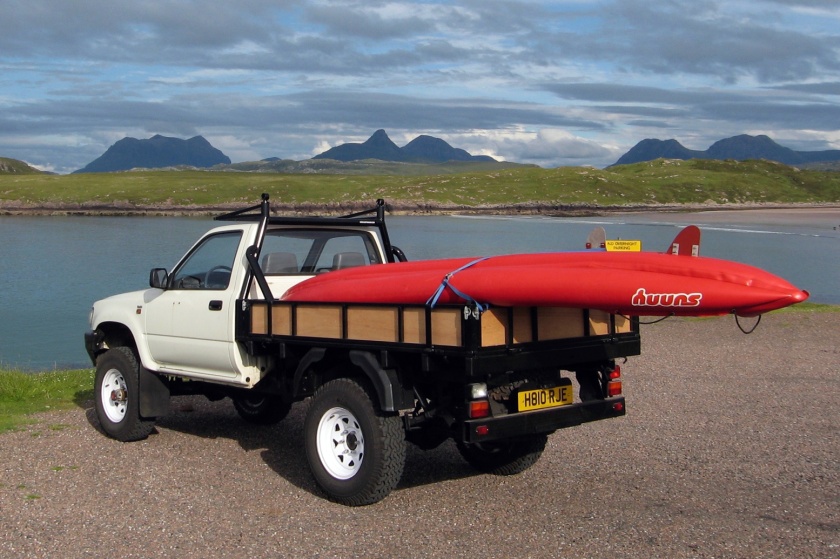

Always liking to try something new, for this trip I’d bought myself a Volkswagen Taro – basically a badged Hilux 2.4 D from the early 90s. After several Cruisers the Taro was a very light ride and with 80,000 kms on the clock was in great shape. The original tray was missing so I got a mate to build a steel-framed plywood flat bed, cleverly modify the chassis to hold two spare tires, fit some BFGs, a Kenlowe fan and a set of OMEs all round to help carry of fuel and water across the Quarter.

I set off for Morocco as confident as I could be that my untried rig was up to the task. But when venting a thick black plume of soot while pegged out in second gear over Spain’s 10,000-foot Sierra Nevada, I did wonder if the little Taro would budge once faced with the Ouarane Sand Sea and an extra half ton on board.

Ron, Sue and Roger turned up a day late at out rendezvous in the southern Morocco country town of Tata, having been pushed back by mud slides and floods taking a high route over the Atlas. After a quick chicken and chips we set of south towards the Atlantic Highway and Mauritania.

Halfway down Sue suddenly had an idea for a protocol we should set up should we hit trouble. A mutual friend of ours back in the UK had contacts in the security services and so we tracked down a working fax and explained how we’d text him at each key stage of the trip. We’d been advised not to use our sat phones in Mali which we would be crossing ‘unofficially’ for fear of the calls being picked up by spy satellites and resulting in the dispatching of an unwanted patrol or drone. It may all sound very ‘James Bond’ but a year earlier the US had launched operations like ‘Enduring Freedom – Trans Sahara’ (OEF-TS) and the ‘Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Initiative’ (TSCTI) to try and ‘protect borders, track movement of people, combat terrorism, and enhance regional cooperation and stability’.

One particular guy they were after (and we were hoping to avoid) was Moktar ben Moktar (left), an Algerian-born emir holed up in northern Mali running a smuggling operation of not-so-soft goods. More brigand labeled a terrorist back then and as damned elusive as the Scarlet Pimpernel, his smuggling heyday was on the wane but as we were to find out, events in northern Mali were to set him right in our path.

With out man in the UK on standby we settled back for the long drive to the Mauritanian border. Just south of Layounne we filled all our tanks with the last cheap fuel from Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara. I’d picked up an 50-gallon drum for nothing while Ron had ‘tiled’ his 60 with a carpet of jerricans. Roger and Sue had a built-in 400-litre set up. If the pump attendant was on a commission he was having a pretty good day, while for us it was an opportunity to find out how our rides performed at near-maximum payload. With relief my Taro still managed to pull up the odd incline without protest. Perhaps the Sand Sea would not be the death of it after all…

A year or two ago the Chinese – the new best friends of many African nations – had blitzed a new coastal road from the south ‘Moroccan’ border to the Mauritanian capital of Nouakchott, so completing the first sealed north-south route across the Sahara. That meant border formalities between the two countries had eased up (it wasn’t to last) and we slipped out of one country and into the other in just a couple of hours.

Now in Mauritania, we set ourselves a 350-mile off-road run to Atar over small bands of dunes alongside the iron ore railway. As is often the way, no matter what your experience or tire pressures, you often get stuck on the first dune day until you re-acquire a feel for the machine. For some reason too, crossing the border saw temperatures jump into the 30s. Luckily the wind was in our face (as it would be for the entire crossing) and I at least drove my VW on the temperature gauge with the Kenlowe whirring away. With our half-ton loads, all our vehicles were working hard and after traversing each bands of dunes we’ll pull up the hoods to give them a breather.

Expecting my little 60hp four-cylinder to be getting a thorough wringing, I’d bought some 50W oil and one hot evening set about changing it. One time years ago a chronically overheating Land Rover 101 had been transformed by running the engine on axle oil. This time the Taro’s gauge didn’t register much of a difference but every little bit helped.We took a cross-country excursion to cut a corner – always a thrill – and by rejoining the main piste and crossing a couple of escarpments arrived in heat-struck Atar at the base of the Adrar plateau in time for our rendezvous with Mohamed.

He turned up a day later outside town but too scared to come in. Despite adopting the shaven-headed Moorish appearance and ubiquitous blue robe, Mohamed’s Algerian ID had given him a rough time through southern Mauritania. And that wasn’t all. Following rains and tyre-destroying double punctures he’d also knocked out his low range and subsequently stressed his clutch on the way past Timbuktu. Then the guide he’d lined to lead us across eastern Mauritanian had been recognized as a former rebel and was ejected from Mauritania where he was wanted for a raid. Successive checkpoints had cleaned Mohamed out forcing him to drive by night to avoid the bribery, but the replacement guide he’d hired to get him to Atar was out of his depth. Or so the story went… Back home many had warned him that the crossing was not worth the risk, even for a free VX, but to his credit Mohamed too saw the simple appeal of a desert adventure.

Next morning we did the Big Fill Up – fuel, water and food to last us two weeks and up to 1600 miles across trackless and waterless desert; an extreme range even by Saharan standards. Ron’s old 60 was cooking on the ascent onto the Adrar plateau, Mohamed’s brakes were seizing on, cone washers were falling out of his rear hub and my Taro was not setting any land speed records on the upgrades either. Only ‘Eric’, carefully maintained by Roger over 15 years or more trundled quietly along.

We were not the first to attempt this particular traverse; we were probably the second. Clued up Landynistas will know that in 1975 Tom Sheppard led the Joint Services West East Sahara Expedition (‘JSE’).

A couple of months earlier I’d spent half a day at the Royal Geographical Society’s library studying the expedition report, jotting down their waypoints laboriously gathered with sextants and almanacs twenty years before GPS came on the scene. Back then, running the Rover V8s down to 4mpg, the JSE had to carry huge fuel loads all the way from the coast. With our diesels we were expecting more like 14mpg at worst which dispensed with the need for the JSE’s trailers or air support.

A hundred miles from Atar ruined medieval dwellings spilled down the escarpment at Ouadane, the last town. While taking lunch under the last trees, Mohamed placated the soldiers at the nearby checkpoint, telling them we were on an innocent day trip out from Atar. In fact we were heading the other way, east into the Majabat and out of Mauritania without any formalities. This sort of persuasion was exactly the reason I’d hired Mohamed, a nd it wouldn’t be the last time he’d help us out on this trip.

I’d kept our exact route quiet as I knew well that both the Dakar Rally and fellow travellers had been ambushed in remote areas when detailing their intentions too clearly. In fact, for want of anything better I planed to follow the JSE’s tracks into the Ouarane Sand Sea. This initial combination of dunes coupled with maximum payload would be the crux of the trip but however daunting, if the JSE had managed it with towing 101s, then so could we.

About an hour from Ouadane we left vehicle tracks for good and camped on the virgin sands, on the south side of the huge Guelb er Richat formation. Viewed from sat pics people often assume the Eye of Africa’s concentric rings thirty miles across to be a huge impact structure. In fact Guelb is merely an uplifted and eroded dome pushed up by a magma plume from below, a sort of low-energy volcano.

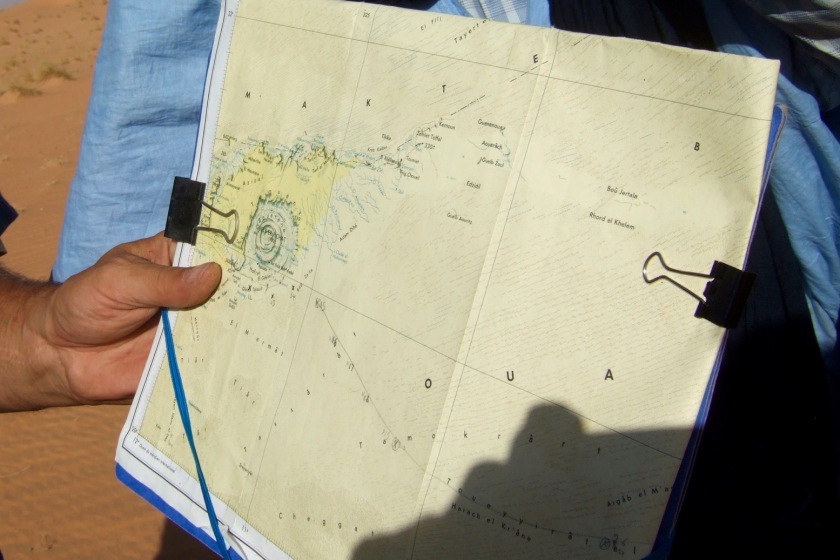

Studying the maps and sat images yet again that evening, I realized I’d made a small navigational error. In a hurry to get going eastwards I’d not led us far enough south as the JSE had done to escape the outer rings of the Guelb. It underlined the meticulous attention to detail they’d made back then and how lazy we can get simply linking up the lines between GPS waypoints.

Were the outer rings truly mini-escarpments as depicted on the aged French maps, or could we find a passage through? How much fuel would it consume? And what about the unseasonally high temperatures which would reduce our water range, or the 20-mile dog-leg we’d have to take through the dunes that had taken the JSE two days? After all that, Mali had a whole different set of potential dangers. In Atar we’d received bad news. Backed by Algerian and probably US support, the Malian Tuareg in northeast Mali had turned on Moktar ben Moktar and his crew, pushing them back west in a series of skirmishes directly into our path.

These thoughts gnawed at me that night with troubled dreams, a measure of the pressure I was under as we stood at the rocky shore of an ocean of sand. I hadn’t had it this bad for years, but dawn brought the unavoidable need for action and we drove into the sun as it rose over the outermost rings of the Guelb, bound for a distant JSE waypoint. We rode the undulating terrain, sometimes sand, sometimes rock, sometimes soft car-trapping sebkha or claypans where transient rains had pooled in the depressions between the ringed ridges of the crater.

Up ahead a power-sapping sand slope rose up 150 feet to a rocky cliff the height of my car; no way through there. I turned south to run clockwise around the vast crater rim, looking leftward for a gap. A few foot recces proved fruitless but eventually the terrain gave way; Mohamed spotted a car-wide ramp and went for it, accelerating hard to pop out onto the sands, free at last of the Guelb’s clutches. We snicked into low range and followed him up.

Ahead of use lay the sands of the Ouarane; low intermittent dunes aligned around 60° east of north and which rolled unbroken for 300 miles to the Mali border. The sand ridges were separated by easily navigable corridors. The technique would be to follow a corridor ENE while taking the chance to hop over any navigable passes between the dunes to the south to maintain an easterly bearing, the most direct route. At first I was too preoccupied chasing JSE waypoints, figuring they were the key to the maze, while also half hoping to come across 30-year-old traces of their passing. But after a while I saw, as Tom might put it ‘the big picture’ and figured any way east was good: navigate ‘ground to map’ not the other way round.

Traversing the rolling sands in the corridors we all had our share of boggings, most usually when the lead car mired in an unseen soft patch which the rest steered round, or when we took our southward hops over the dunes. Mohamed’s 80 seemed particularly prone, due we decided later, to the diesel conversion not being well matched to a petrol transmission. The over-geared wagon lacked the torque at key revs to pull itself through. In the meantime we’d christened my VW El Ghazal; the gazelle. For the first time I discovered the blessings of modest horsepower. The four-litre Cruisers all had the power to get well and truly stuck; the Taro, probably half-a-ton lighter and with half the power, baulked early and could be backed out to find another way. No one was more surprised than I when I was able to lead the heavy Cruisers over and around the crests from one ridge to the next.

A wind stirred up from the northeast, finally cooling temperatures but also reducing visibility and as always, bringing the worry of an all-out sand storm. After a while banks of grass covered the sands, making for rough going over the tussocks. Anywhere else this place would have long ago been grazed to a dust bowl but out here, far beyond the range of the nomads’ camels, the thick grass grew unseen, withered and died.

Somewhere along our route a Comanche aircraft had dropped in on the JSE to replenish their fuel. The report detailed how they crew had laid out an 1100-metre runway in a dune corridor. Wherever it was, the winds of three decades had long since blown away any traces and not so much as a half-buried oil drum remained.

After two days we reached our first goal: N20 43.5’ W08 50.7’. It didn’t look much different from anywhere else around here; a corridor of undulating sand between higher but now more spaced out lines of seif dunes.

This was the point where on the 9th of February 1975 the JSE had decided to make their run ‘across the grain’ of the dunes; 20-miles as the crow flies to the southern edge of the Ouarane Sand Sea and the flat sand sheet beyond. On top of the demanding terrain, vehicle problems meant it had taken them over two days to make that crossing, taking a zig-zag course around the dune peaks.

After months of trying to visualize the scene, our Saharan Rubicon did not look too bad. Some dunes were high it was true, but big dunes usually take linear formations with clearly defined passes and wide corridors. Small dunes like Algeria’s Grand Erg were much worse; a dense chaotic mass of crests and pits like storm-tossed waves.

Inspired by our good progress so far we checked the tires were down to one bar and set off in the cool after dawn towards the first ridge, paused and turned left and then right to slip between the wind-carved summits. Another corridor, another sand slope and, always keeping to the high banks to keep a decent in hand should the sand soften, I worked my way around the barriers. When stuck I backed out while someone else went off to explore an alternative route. We worked out way south with surprisingly little drama but as I hopped from dune to dune a light mechanical knock I’d dismissed as axle play became increasingly prominent. Revving in neutral proved that is wasn’t some worn CV. I called Mohamed over for a listen. Tapping the throttle his face dropped, it was a sound he knew too well: a crankshaft bearing about to meet its end.

During our crossing we collected dust samples and imagery for Oxford University’s Climate Research Lab. Dust from the Empty Quarter (red areas, right) is thought to have an important effect on the global climate, but has never been obtained or analysed before.

During our crossing we collected dust samples and imagery for Oxford University’s Climate Research Lab. Dust from the Empty Quarter (red areas, right) is thought to have an important effect on the global climate, but has never been obtained or analysed before.

You must be logged in to post a comment.