Originally published in Overland Journal

See also:

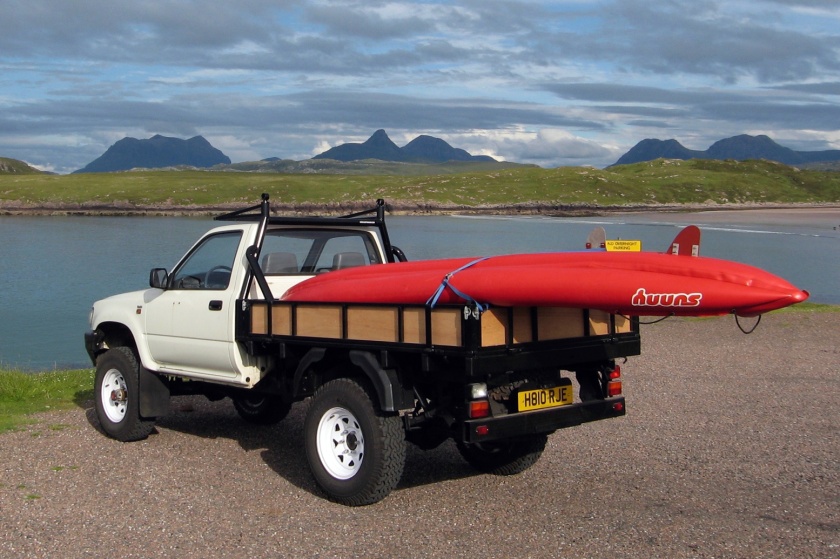

VW Taro build

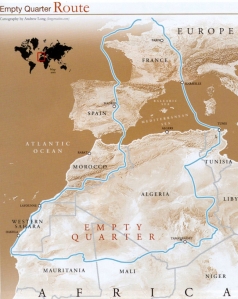

Intro

Part 1

Many times during my decade of despatching in London I’d longed for the irritatingly reliable engine of some middleweight Honda I’d ridden day-in, day-out for years to explode into a thousand pieces. Nothing less than a terminal meltdown with conrods rupturing the block and cogs spitting out of the muffler.

Now, a long way from the interminable Clerkenwell Road, I was faced with the inevitability of my VW Taro’s imminent demise. The engine knock might last for days, but in reality I knew its sudden escalation meant this car would not see another dawn.

At least the dreaded dune crossing had turned out to be an anticlimax. It was all over before we realized and ahead of us the ridges subsided into a rolling sand sheet. We could now resume our easterly course towards the Malian border.

Our convoy followed me as I nursed the VW along, keeping the revs low and the load light. For a while I thought it might make it, but make it where? We were just at the start with a thousand vacant kilometres of Empty Quarter to cross. Mile by mile the ear-wincing clatter grew louder until a hideous hammering suddenly filled the cab as I tiptoed out of a shallow sandy bowl. I stamped on the clutch pedal and cut the engine, but of course this engine had just switched itself off, big time. We’d reached the VW’s grave.

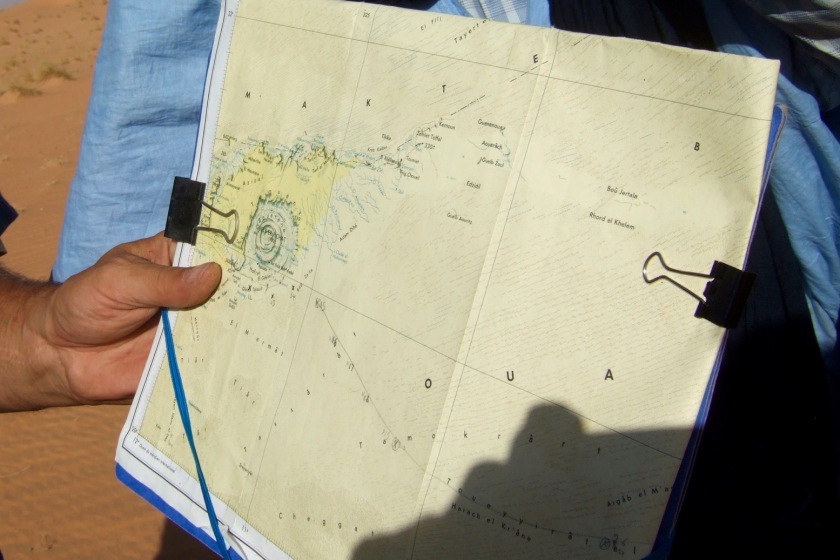

If you’d asked me to point out the least desirable place to have a serious breakdown on this trip I would have guessed somewhere beyond the dune crossing but before the full traverse of Mali; somewhere like N20°03′ W08°00′, give or take a hundred clicks. From this point the nearest towns of Nema, Chinguetti or Timbuktu in Mali were as far as they could be: the better part of a week’s round trip.

I rolled back down into the dip where we hitched up the front end and pulled off the sump, expecting to find it full of shrapnel. No such drama although a bit of prodding revealed #4 big end was definitely shot. I had no spares of course; these days if you think you ought to carry new big end shells for a Sahara trip, what you really need is a better car.

We cleaned ourselves up and considered my options. We could wait here for a week, eating into our supplies while someone headed off to track down a big end. With the right part I might be able to limp on before making a proper repair in Algeria. But judging by the sudden, pre-terminal racket the crankshaft could have snapped – a distinct possibility as the engine was locked solid. Establishing this would be a lot of heavy work in the middle of the desert; dumping the car or trying to recover the remains made more sense.

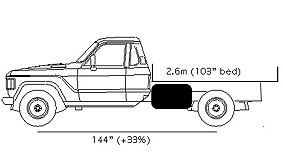

The problem with dumping it was there was literally no space for me in the other cars, let alone my gear, which now had a value greater than the pickup. And with a replacement engine from somewhere, the VW – which was otherwise in great shape – could ride again.

We got on the Bat Phone to the Ambassade on the far side of the Quarter. A truck had just left Timbuktu but with a full load, while an empty up north near Taoudenni was having gearbox problems. They’d have a think and call back in a couple of hours.

Presently the phone rang. There was a MAN in the yard but the 2000-kilometre round trip would cost as many euros. It would take a couple of days to track down enough fuel for the round-trip too; after that they’d meet us in three days. It was marginal but I figured along with the convenience of getting my gear to somewhere useful, there was a chance of getting the pickup re-engined or sold on. Calling in a recovery from Timbuktu was not an option; we’d blow our cover in Mali with who knows what consequences, most likely with the waste of a lot of time and money while losing our chance to finish the crossing of the Empty Quarter.

With the recovery underway we put on a brew. A little later Ron came back from a wander, having found various Neolithic trinkets: flint knifes and hand axes from several thousand years ago when hunter-gatherers roamed what would have then been a grassy savanna teeming with game.

Did the disaster bother me? Not really. Vehicles are best treated as expendable in the Sahara, on this trip more than most. My desert travels had gone rather well these past few years so I was due for a calamity; it just wasn’t the one I was expecting out here. The crux was not being alone and having back-up plan from a place like the Ambassade. It was a shame to waste all the work and money put into building up the Taro but it had got this far and, for a gutless old ute, the gazelle had proved itself up to the point when it croaked.

By next morning we were already getting restless, and with the thought of a week’s waiting for the lorry to trundle over the eastern horizon, the tricky topic of towing re-emerged. It was clear that only the VX was capable of it: Sue didn’t mind but Roger was less keen. I saw his point; towing even the lightened ‘gazelle’ across unknown terrain for a thousand kilometres was a shortcut to prematurely ageing the transmission; I knew desert travellers who’d found this out the hard way. In the end though, the call to action prevailed and a fee of a euro per kilometre was agreed. I dished out the masses of fuel I had left and divided my kit for burning or portage. With the pickup as light as it could get, we roped a kinetic line to the VX and set off.

They say never tow with a KERR, it will ruin the rope, but I can tell you the elasticity is most welcome when a torquey VX is yanking you from one tussock to another hard enough to give you whiplash. Unless you’re a lost camel with an appetite, these tussock fields, stretching for miles at a time, are the bane of this part of the Sahara. In between them I relaxed on the rolling sand sheet and even had a chance to shoot some video reports. As we alternately cruised and bounced along I was surprised to see fennecs (desert foxes) dashing out from their holes.

Inevitably we hit a soft patch and spent half an hour getting the running cars out before we could even turn our attention to the dead pickup with much digging and all the tow ropes joined together. But progress was good and by lunchtime next day we pulled up at 20°N 6°W to record the point for confluence.org, a website that’s collecting images and descriptions from every terrestrial longitude and latitude confluence on earth. Our shots to the four points of the compass were all interchangeable: blue sky over flat sand sheet whichever way you looked.

This point also marked, near enough, the border with Mali and our entry into the badlands of the ungovernable far north. Sure enough we soon crossed the fresh tracks of a single vehicle heading north far off any recognised route. Whoever they were, like us they didn’t want to be seen. That night we camped out on the wide open sand sheet with no lights.

The next couple of days would be tense. At one point around 3° 40’W we would have to cross the widely braided Timbuktu-Taoudenni salt route. Although its meagre traffic would probably be legitimate, it would be a whole lot better not to have our incongruously eastbound convoy seen by anyone. If we did get hijacked the raiders would have quite a jackpot; and as we were soon to find out, they were closer than we thought.

As the sun rose next morning a lone dove flew into our camp and staggered around. I’d encountered such bird behaviour before in the desert and presumed they were stragglers, weakened during the southward migration and close to death. But once we got going again all thoughts of the lost dove were shaken out of me as we hit another interminable band of tussocks. The problem was when the VX steered around a lump, the pickup got towed on a direct line. Result? Head-shaped dents in the roof of my cab.

By mid-morning Mohamed received a text that the lorry was already in the area. Amazed by its swift progress but preferring not to use voice calls in case it set off any alarms down south, we texted back our position and waited.

For hours we listened intently over the wind for the growl of the big engine. What was taking them so long? After a few false alarms we finally spotted the sand-coloured MAN trundling past a couple of miles away. Ron hopped into his 60 and dashed out after them.

Their transit of northern Mali had not been uneventful. The previous evening they’d been held up by gunmen in a lone Cruiser and relieved of a drum of fuel and the power lead for their Garmin. Once the batteries had expired they’d had to locate us with the basic GPS in their sat phone which had no handy ‘go to’ feature. The two drivers, truck owner Hassan and his mechanic didn’t seem too perturbed by the robbery. Luckily they were empty and had wisely not disclosed the nature of the mission. They still had the truck, a 19/240 troop carrier specially built for Algerian desert forces in the 1980s and now the long-range desert smugglers’ choice over the more complicated and expensive Mercedes.

We set about finding a way to load the VW. A mile or so away we found a hardened platform of calcrete – the weathered remains of what geologists call duricrust which here had one edge exposed by the wind a couple of feet proud of the desert floor. By digging two wheel channels into the crumbly edge, the lorry could back up almost level with the car positioned up on the pan.

A couple of hours later we’d all taken our spell with the picks and the levels were closing up. Some firewood and sand plates made a ramp and with a run-up the pickup rolled into the back.

When it came to lashing down you’d think these guys knew their business; it didn’t look like it. My tyres were deflated (to reduce rolling I presume), heavy fuel drums were then piled on the Taro which was then secured over the lorry’s flexing side gates which was to do a lot of unnecessary damage to both machines over the next few days. But no one listened.

At just about every stop within the Empty Quarter, we easily found prehistoric artefacts and geological oddities lying near the camp. Among them were pieces of fulgarite – sand fused into delicate coral-like tubes or flakes of glass by lightening strikes. It’s something that never ceases to amaze me – solidified lightening. In Egypt we once found a rod of fulgarite as thick as my arm twisting deep into the sand in a shallow helix form created as the charge earthed itself.

By towing from Mauritania we’d saved the truck a good 800 kilometres and a few days so Mohamed was working on Hassan to try and reduce the price. It wasn’t looking too promising. Like Mohamed, Hassan was a Berabish, the little-known Arab tribe from around Timbuktu, descended from the tail end of the Islamic conquest which had whipped across northern Africa in the 8th century. Essentially Moors, and notoriously sharp in their business dealings, the Berabish run much of the bush commerce in that region. Unlike the better-known Tuareg (whose ethnicity Mohamed feigned as it was good for business in Algeria), they have no time for either playing up to tourists or making rebellions, unless there’s good money in it. Getting a financial break from Hassan would cost the proverbial pound of flesh.

One of the truck drivers was particularly aggressive at the wheel so I took to sitting in my car to try and limit the damage. Leaking diesel drums had the pickup it sliding around on its flattened tyres, the sidewalls getting further pounded by the rims’ edges as the VW bashed against MAN’s sides.

One of the truck drivers was particularly aggressive at the wheel so I took to sitting in my car to try and limit the damage. Leaking diesel drums had the pickup it sliding around on its flattened tyres, the sidewalls getting further pounded by the rims’ edges as the VW bashed against MAN’s sides.

I persuaded them to part re-inflate the tyres but all my gear was getting either crushed by the drums or soaked in diesel. As the side gates bent inward, the ropes slackened and the car beat itself up. I’d have to crawl out of the window, edge over to the MAN’s cab like Indiana Jones and thump on it until they stopped. They’d hop out and hang off the ropes to get them good and tight against the creaking side gates. It was painful to watch, but on the move the grunt of the 240-hp truck was something to behold. Rated at 19 tons but carrying only a fraction of that and running singles on the dual rear axle, it ground its way over small dunes like a digger.

Presently we started bisecting the salt route’s countless north–south tracks, the only piste we’d see in the Empty Quarter. An hour later as they began to peter out I spotted a distant MAN on the southern horizon, probably heading back to Timbuktu with a cargo of hand-hewn salt slabs from the pits at Taoudenni.

Despite my troubles we had not forsaken our commitment to the advancement of climate research. Learning of our plans to cross this remote region, a scientist friend back at Oxford University had asked if I could collect dust samples from a couple of ‘hot spots’, the darker red patches above.

The Sahara is the world’s biggest source of dust which, when launched up into the atmosphere by seasonal windstorms, is thought to have a significant effect on global climate, including Atlantic hurricanes. After western Chad, much of this dust comes from the Empty Quarter but samples had never been obtained before. As we passed through one of the hotspots, composed of the same calcrete we’d dug into a loading ramp, Sue interpreted my gesticulating from the cab and stopped to collect some samples.

Next afternoon we passed the place where the truck had been ambushed on its way out, and later spotted our first tree since Ouadane in Mauritania. Soon rocky hills rose out of the unending sand sheet, heralding the outliers of the Jebel Timertine.

We joined a piste and as the sun dropped behind us we rolled into the compound known as l’Ambassade in the No Man’s Land trading post of Il Khalil. Bou who managed the place gave me a warm welcome, especially when I handed over a solar panel and some Garmin 72s I’d promised him.

New big end shells had been ordered in from Algeria and gritty negotiations with Hassan got underway. The Taro was now in a sorry state but he was unapologetic. Nevertheless both he and Mohamed were interested in buying it. In no mood to do Hassan any favours, I let Mohamed have it for the combined cost of the recovery, Rog and Sue’s towing fee and a haircut in Tamanrasset. A total loss in other words, but better than expected considering my helpless position.

The VW was shoved into a corner, had is wheels removed and locked in the storehouse and was covered in a sheet. It’s probably still there today, but full of bullet holes, as Il Khalil ended up on the front line of the current war and got bombed by the French.

As ever, the chirpy Bou was full of business ideas. Could I ship a container full of Land Cruiser or old Land Rover parts out to Togo, or maybe we could slip a brace of Renault prime movers up into Algeria, how much are they in France anyway? And what about three double-cab Hiluxes? I said I’d find out and get back to him.

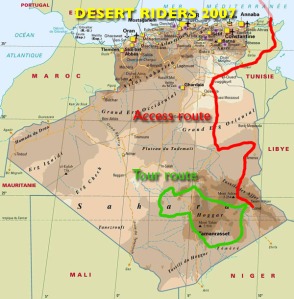

We’d crossed the Majabat, some more successfully than others. The Mauritanian guide who’d been out of his depth got paid off, and I took his place in Mohamed’s 80 as we headed for the Algerian frontier at Bordj Moktar. After their epic crossing, in 1975 the JSE had been turned back near here and sent down to the Sahel to continue their eastward traverse to the Red Sea. We weren’t going that far but insh allah hoped to range a little further across the width of the Sahara.

But our entry into Algeria was no forgone conclusion. How were we to explain our unused Malian visas? I’d already considered this and figured the worst they might do is send us down to Tessalit, the nearest Malian entry post 120km away and, with Tuareg bandits on the prowl, a risky proposition according to the Ambassade’s travel advice unit.

It was time to face the music so we rocked up at the Gendarmerie at Bordj, handed over our passports and let Mohamed schmooze the cops. He knew well it was the best way to get the better of the countless ‘Men in Hats’ you have to deal with in Algeria, but it didn’t look good. Under orders from the Free World to seal its massive and porous southern borders as best they could, what were they to make of a bunch of tourists blithely roaming across Moktar bin Moktar’s territory? The brigade commander was already on the phone to Tamanrasset, 600km away, when by chance Mohamed recognised an officer from In Salah, his home town. The guy was swiftly persuaded to vouch for Mohamed’s peerless credentials as a renowned desert guide and with, as far as Algeria was concerned, all the correct paperwork and permits in place, we were grudgingly let off the hook.

It had been a lucky break and an example of why it had been worth hiring Mohamed. In sub-Saharan countries like Mali and Niger a tourist might pay their way out of situations like this, but in Algeria I knew well (and have found out again since) that bribing small-time border officials is not done. It’s actually one of the things I like about Algeria.

‘Al hamdullilai!’ (‘Allah be praised’) exclaimed Mohamed, delighted to be back home after his fraught round trip to Mauritania. We had crossed Le Quartier Vide, evaded the attentions of Moktar bin Moktar and his henchmen (well, almost) and were safely back in the land of milk, honey and cheap diesel.

After a celebratory feast at a friend’s house (for which we’d all start paying very soon), we headed northwest for Tamanrasset and the Hoggar, retracing the route I’d taken with the burgundy VX a few weeks earlier.

On the way we diverted to the gorge of Tim Missao (above) which I’d not visited since the 1980s in my 101 (left). The gorge is a lovely spot and represented the most animated topography we’d seen since the Guelb near Ouadane. We decided the Empty Quarter was aptly named. It made up one of the biggest sand sheets in the Sahara, void of trees, outcrops any higher than my knee and even significant sand seas. Algeria on the other hand was full of diverse landscapes: smooth granite monoliths, gnarly volcanic ranges, eroded sandstone escarpments lapped by sand banks, and of course sand seas that would cover Belgium.

It was one reason why I returned here again and again. Another was that while exploring the gorge, the ever-observant Ron easily found the paintings of Garamantean horse-drawn chariots I’d missed on previous visits. The ancient rock art suggested that some two millennia ago traders from this mysterious civilisation based in southwestern Libya may have ranged much further across the Sahara than previously thought. In late 2007 similar discoveries near Jebel Uweinat in the far northwest of Sudan may do the same for the hitherto Nile-bound Ancient Egyptians.

Whether it was the stress relief or what we ate in Bordj, for us Tamanrasset passed by in a three-day blur of dozing and scurrying back and forth to the toilet block. Once the worst was over, Mohamed headed back north to In Salah and we got a change of crew for our final leg, east to Djanet.

The two new guys made me realise how lucky I was with Mohamed. To them, and many other guides, Mohamed’s crossing of the Quarter with us was seen as madness. Why risk your car out there when you could earn safe money transporting regular tour groups across the Hoggar and Tassili N’Ajjer tram lines? For all his faults and bullshit, Mohamed enjoyed a true adventure much like ourselves. We may never choose to go there again, but with his help we’d seen it for ourselves.

Already a warm, retro -spective rosey view of northern Mali’s barren sand sheet was setting in. Now it felt frustrating to be hemmed in along washboard tracks. Still, one look out of the window made up for it: the shark’s fin blade of Areggane mountain, the sand-swept canyons and rock arches of Tagrera, circular paved pre-Islamic tombs I’d never noticed before, and steps carved eons ago into a rocky sentinel that Ron had discovered on a previous trip. Our drivers had to be persuaded to make the deadly 20-kilometre diversion off the track into the unknown and once there, feigned indifference.

It was early December now and the weather was turning. Frost coated my sleeping bag after a night beside the Erg Admer dune passage which led to the oasis town of Djanet. By early afternoon the cars had clawed their way onto the dune slopes to the crest from where the tawny Tassili N’Ajjer escarpment unrolled across the northern horizon. In no hurry to reach town, we camped earlybelow the cliffs, cooked up the best of our remaining food and watched the same full moon rise as it had done over our first camp together in Morocco, four weeks and nearly as many thousand miles ago.

In Djanet next day we organised a day trip up to the Jabbaren rock art site up on the plateau. A car collected us before dawn and as the sun lit up the Erg Admer dunes behind us, we were already panting steadily up the goat track that led to the plateau top. As we trudged up, a lone figure scampered down with a cheery salaam. Behind us a hoard of bedraggled ‘illegals’ from sub-Saharan Africa had emerged fro the rocks, following our path uphill. Dropped there overnight by who knows who, they’d been instructed to wait for the guide who’d lead them across to Ghat in Libya, two days away. From there they were expecting to get to Malta and mainland Europe, but likely as not would get deported in one of Libya’s periodic purges. Less than a decade later Gaddafi had fallen with other North African despots and the trickle of migrants became a tsunami.

Even back then, it all put our own adventurous caper into perspective, but we were still pleased with ourselves. We’d driven laterally across as much of the Sahara as was possible without ensuring serious trouble and our own deportation. Now it was time to head north.

During our crossing we collected dust samples and imagery for Oxford University’s Climate Research Lab. Dust from the Empty Quarter (red areas, right) is thought to have an important effect on the global climate, but has never been obtained or analysed before.

During our crossing we collected dust samples and imagery for Oxford University’s Climate Research Lab. Dust from the Empty Quarter (red areas, right) is thought to have an important effect on the global climate, but has never been obtained or analysed before.

You must be logged in to post a comment.