See also

Shell Guide to the Sahara (1955)

From 1949 (the year an Austin A70 traversed Africa north to south in a record 24 days) the Automobile Association of South Africa published their trans continental route guide until this final fifth, fully revised edition in 1963. In its way, Trans-Africa Highways is a more basic version of the French Guide du Tourisme Automobile du Sahara published from 1934 to 1955. You can buy copies online for 15 quid.

By 1963 independence from colonial rule was in full swing right across Africa, presumably making researching and producing future editions too costly. By 1963 it would already have been beyond the time when you could drive just about anywhere with a wave and a salute, as first rebellions and independence and then all-out civil wars impacted on transits.

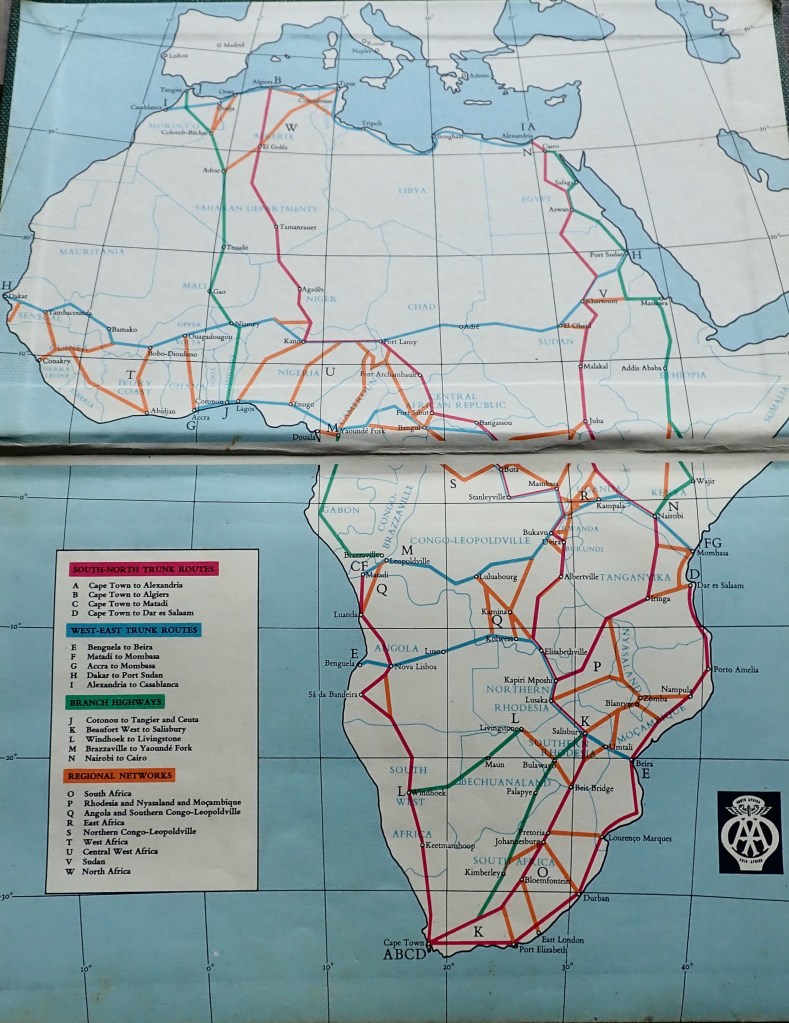

The colour map on the inside cover (below) shows nearly two dozen driveable routes, including four north–south trunk routes: Cape Town to Matadi (DRC), to Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), and all the way north across the Sahara to either Algiers / Tangier, or Alexandria on the Mediterranean.

Unlike today, regular cars like the 1954 Morris above, were deemed suitable, even if they may have required full suspension or engine rebuilds along the way (left). It was all part of the adventure.

Back then the west route avoided Cameroon and Congo Brazza and came across the eastern DRC up to CAR, into Chad and then west to Kano in northern Nigeria. Here you chose either the short but sandy Hoggar route to Tamanrasset (fatal 1954 attempt), or the easier but longer Tanezrouft route to the west (1954 account, also in a Morris). Today’s Atlantic Route was decades away. Both these Morris expeditions mentioned the TAH route guide which must have been indispensable for undertaking a major African crossing.

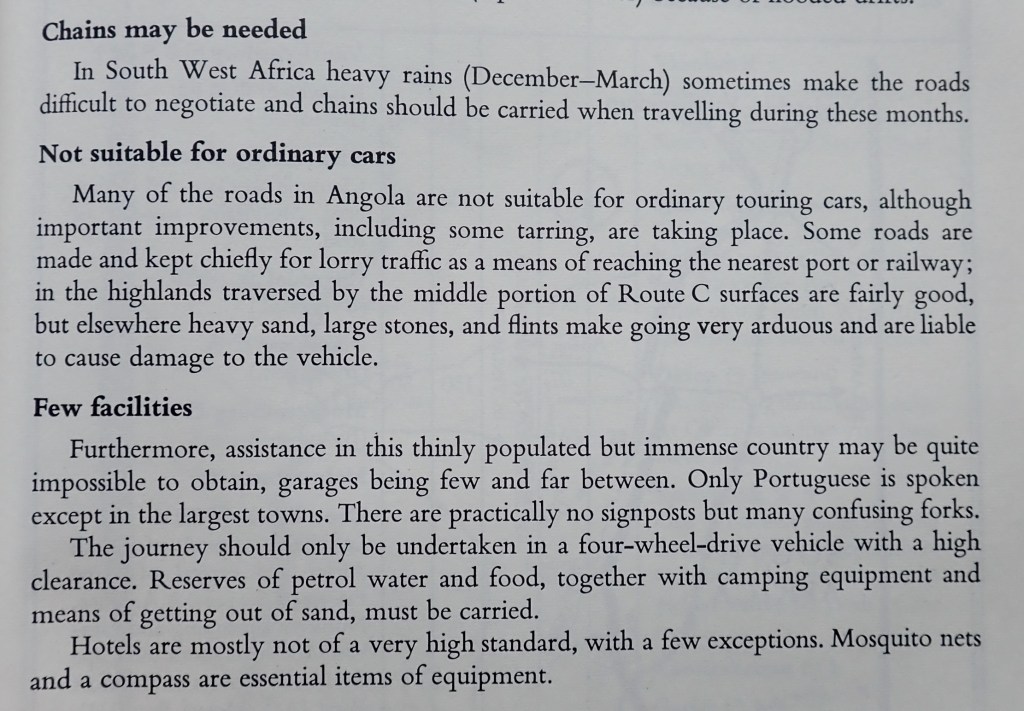

Names like Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Benin and Burkina Faso did not exist in 1963, and the Spanish Sahara and Rio de Oro territories were marked but blank, as no route went anywhere near them. But whatever they were known as now, each country got a brief summary of currency, climate, roads and language, etc. (left)

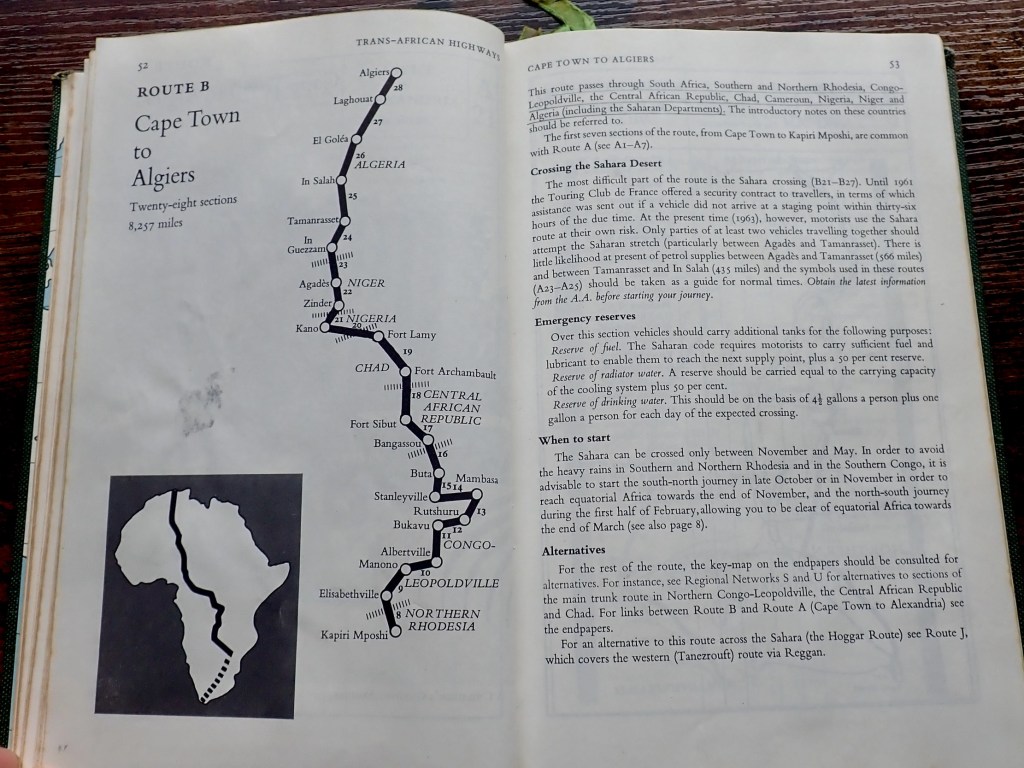

Roues A to Alexandria (6647 miles) and B to Algiers (8257 miles) were the two principle trans-continental axes (below). The latter was the most used and at time of publication the Aswan dam was only in its third year of Soviet-aided construction, so you motored all the way up from Wadi Halfa to Cairo.

Meanwhile, there can’t have been many takers for the 4764-mile run across the width of the Sahel from Dakar to Port Sudan.

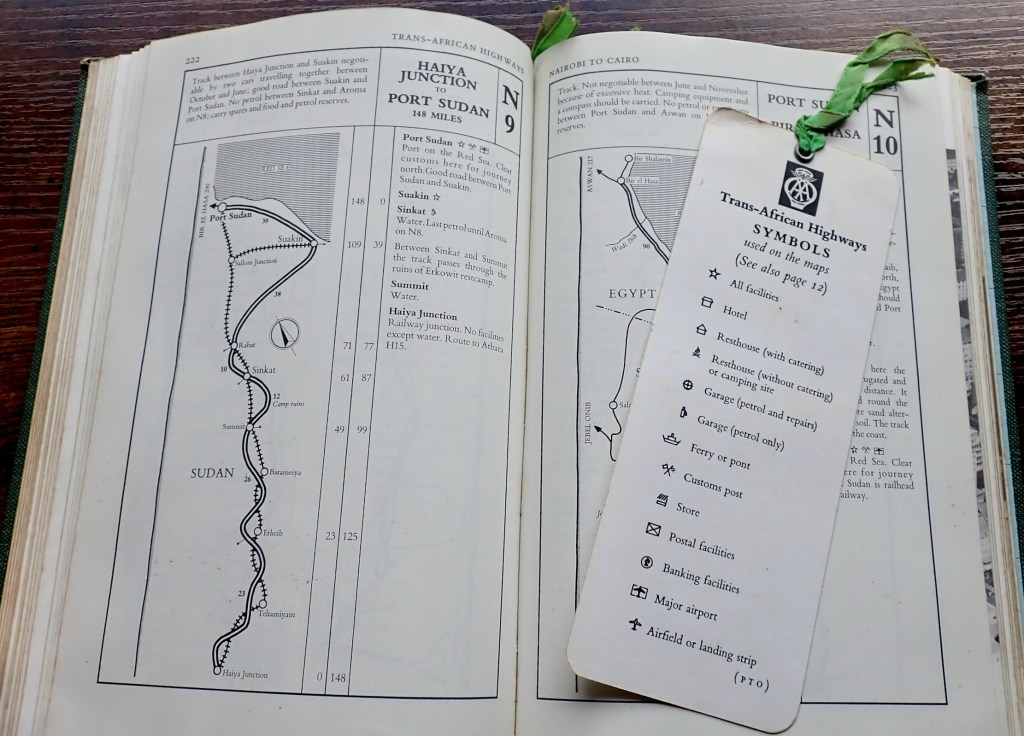

Each route is broken down into annotated map panels of around 200 miles (above) with a summary and icons identifying lodgings, fuel, ferries and so on. You inched your way from one panel to the next, but certainly in the Sahara, marker posts were as frequent as every mile in Mali (below).

Trans-Africa Highways 1963 marked the apogée of an era of motoring in Africa when, outside the French controlled Sahara, borders were crossed effortlessly and many roads and tracks were maintained in superb condition.

Within two decades desert route markers were knocked over, stolen or uprooted, tracks in equatorial Africa deteriorated into deeply carved holloways (left). But another two decades on, the advent of the Chinese roads-for-resources program saw Routes A and B almost entirely asphalted, along with many more.

The major difficulties today in crossing Africa need not be the terrain so that now crossing in modern ‘Morris’ is more feasible. It is the route planning game of snakes and ladders dodging no-go zones, as well as the complex bureaucracy associated with obtaining expensive visas and sticking to schedules. Right now in 2025, only the western route is open; as few as 16 visas from Europe to Cape Town.